Introduction

Elections are foundational to democratic societies, providing citizens with the power to influence governance and policy directions. While the ideal voter is often envisioned as a rational actor making decisions based on careful analysis of issues and policies, the reality is far more intricate. Cognitive biases, emotions, social identities, and information gaps significantly shape electoral decisions. This blog post explores the various factors influencing Electoral Decision Making, with a particular focus on cognitive biases.

Issues: The Ideological Compass in Electoral Decision-Making

For ideologically-driven voters, policy issues serve as the primary guide in their electoral choices, acting as a compass that directs their decision-making process. These politically engaged individuals possess a nuanced understanding of the various policy positions held by different political parties and candidates. They actively seek out and thoroughly evaluate candidates whose policy stances closely align with their own deeply held beliefs and values.

- Comprehensive Understanding of Policy Differences: Ideological voters demonstrate a remarkable ability to discern and analyze subtle policy distinctions between parties and candidates. This keen awareness enables them to make well-informed choices that accurately reflect their personal convictions and political philosophy. Their decision-making process involves a thorough examination of policy proposals, voting records, and public statements to ensure alignment with their ideological preferences.

- Heightened Focus During High-Stakes Elections: The perceived significance of an election significantly intensifies the focus on policy issues among ideologically driven voters. When the stakes are particularly high, such as during presidential elections or times of national crisis, these voters become even more meticulous in their scrutiny of candidates’ positions on critical matters. They pay close attention to pivotal issues such as economic policy, healthcare reform, foreign relations, environmental regulations, and social policies, carefully weighing each candidate’s stance against their own ideological framework.

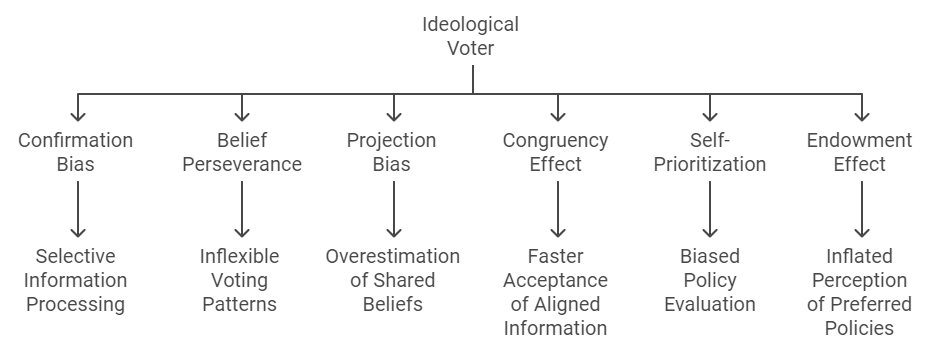

Cognitive Biases Influencing Ideological Voting: While ideological voters often pride themselves on their rational approach to decision-making, they are not immune to cognitive biases that can shape their perceptions and choices:

- Confirmation Bias: This pervasive bias leads voters to actively seek out and readily accept information that confirms their existing beliefs and ideological stance. Simultaneously, they may unconsciously disregard or downplay conflicting data, even when presented with credible evidence. This selective information processing reinforces their ideological position and can create an echo chamber effect.

- Belief Perseverance (Perseverance Heuristic): Ideological voters often display a strong tendency to cling tenaciously to their initial beliefs and policy preferences, even when confronted with substantial contradictory evidence. This cognitive bias can make it challenging for them to adapt their views in light of new information or changing circumstances, potentially leading to inflexible voting patterns.

- Projection Bias: There’s a common tendency among ideological voters to overestimate the extent to which others share their beliefs and policy preferences. This bias can lead them to assume that their views are more widely held than they actually are, potentially influencing their expectations about election outcomes or the popularity of certain policy positions.

- Congruency Effect: Ideological voters often exhibit a predisposition to respond more favorably and quickly to information that aligns with their existing beliefs or expectations. This bias can lead to a faster acceptance of policy proposals that fit their ideological framework, while more time might be spent critically examining or dismissing incongruent information.

- Self-Prioritization in Issue Evaluation: When evaluating policy issues, ideological voters may unconsciously prioritize their own perspectives and needs over those of others or the broader society. This bias can lead to support for policies that align with personal ideologies but may not necessarily benefit the wider population.

- Endowment Effect in Policy Preferences: Ideological voters often ascribe greater value to ideas or policies simply because they are associated with their own beliefs or preferred political group. This can lead to an inflated perception of the worth or effectiveness of policies aligned with their ideology, potentially clouding objective assessment.

This might also interest you: How to Win Votes and Influence Decisions: A Behavioral Psychology Perspective

Illustrative Example: Consider an ideological voter who is deeply committed to environmental conservation. This individual might assume that the majority of the electorate shares their level of concern for environmental issues, leading them to believe that a candidate’s strong stance on climate change and environmental protection will be the decisive factor in winning the election. Even when presented with polling data indicating a shift in public priorities towards economic issues or national security, this voter might persist in their belief that environmental policies will be the key to electoral success. This example illustrates how cognitive biases can influence the perception and decision-making process of ideologically driven voters, potentially affecting their electoral choices and expectations.

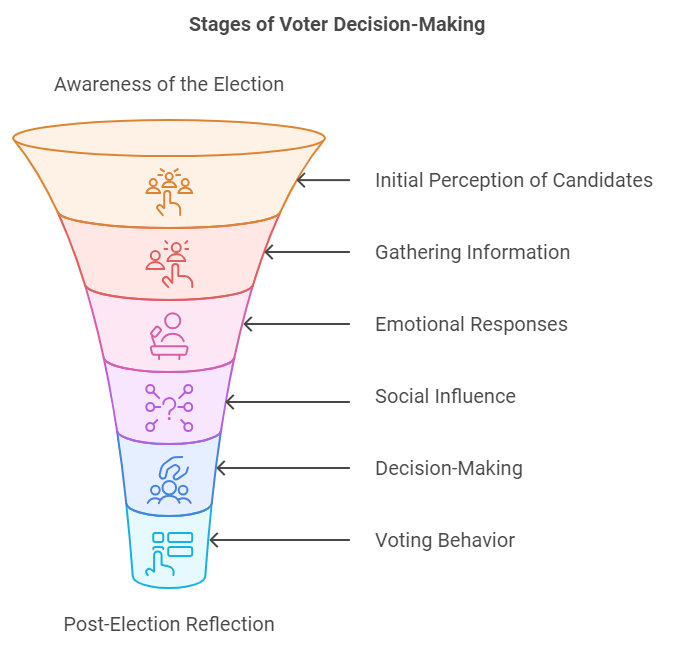

Voter’s Journey: Influencing Factors at Each Stage

Party Identification: The Enduring Compass in Electoral Decision-Making

Party identification serves as a powerful cognitive shortcut for a significant portion of the electorate, offering a streamlined approach to navigating the intricate landscape of electoral choices. This deeply ingrained political affiliation acts as a guiding principle, shaping voters’ perceptions, judgments, and ultimately, their ballot decisions.

- A Resilient Influence: The strength of party identification remains remarkably consistent, persisting across varying levels of ideological sophistication and fluctuating degrees of concern about election outcomes. This steadfast allegiance often withstands the test of time, economic fluctuations, and even policy shifts within the party itself.

- Cognitive Efficiency in Political Navigation: Aligning oneself with a political party significantly reduces the cognitive burden associated with evaluating each candidate or policy proposal individually. This “standing decision” enables voters to make swift choices without the need for extensive deliberation, effectively serving as a mental heuristic in the complex world of politics.

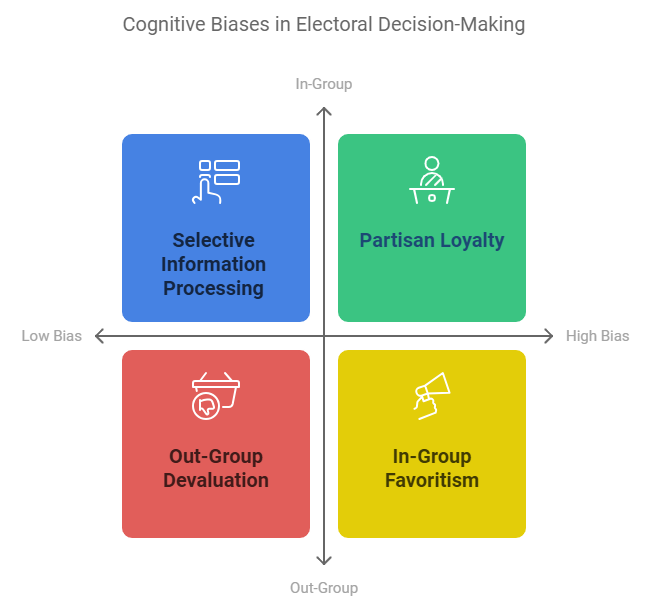

Cognitive Biases Influencing Party-Based Decision Making: Several psychological tendencies interplay with party identification, further shaping electoral behavior:

- In-group Favoritism: This bias manifests as a tendency to view candidates from one’s own party in a more positive light, often perceiving them as inherently more competent, trustworthy, or aligned with one’s values, regardless of objective qualifications.

- Partisan Loyalty: An intensified form of in-group bias, partisanship can lead voters to prioritize party allegiance over objective evaluation of candidates or policies, potentially overriding personal disagreements with specific party stances.

- Out-group Devaluation: This bias leads to the automatic dismissal or skepticism towards proposals, policies, or candidates from opposing parties, even when they might be objectively beneficial or align with the voter’s interests.

- Selective Information Processing: Voters tend to seek out, remember, and give credence to information that confirms their party-aligned beliefs while discounting or ignoring contradictory evidence.

- Party-Centric Value Attribution: This cognitive tendency leads voters to assign higher value or importance to policies, positions, or achievements simply because they originate from or are associated with their preferred party.

Illustrative Scenario: Consider a lifelong supporter of Party A encountering a comprehensive healthcare reform proposal from Party B. Despite the policy potentially addressing many of their concerns, the voter’s strong party identification might lead them to instinctively view the proposal with suspicion or outright rejection. This reaction stems not from a thorough evaluation of the policy’s merits, but from an ingrained bias against ideas originating from the opposing party—a clear manifestation of out-group devaluation and partisan loyalty overriding objective assessment.

Candidate Character: The Intuitive Decision-Making Factor

For voters who are less driven by ideological considerations, a candidate’s perceived character emerges as a pivotal element in their decision-making process. This intuitive approach to evaluating candidates can significantly influence voting behavior.

- Beyond Policy Complexities: Many voters find the intricacies of policy discussions overwhelming. Instead, they gravitate towards making intuitive judgments about a candidate’s personal qualities, such as integrity, honesty, and leadership potential. These character assessments often serve as a proxy for more detailed policy analysis.

- The Power of Emotional Resonance: A candidate’s charisma and ability to forge an emotional connection with voters can be a powerful determinant in electoral choices. For many, this emotional appeal can overshadow policy considerations, leading to decisions based more on feeling than on detailed platform analysis.

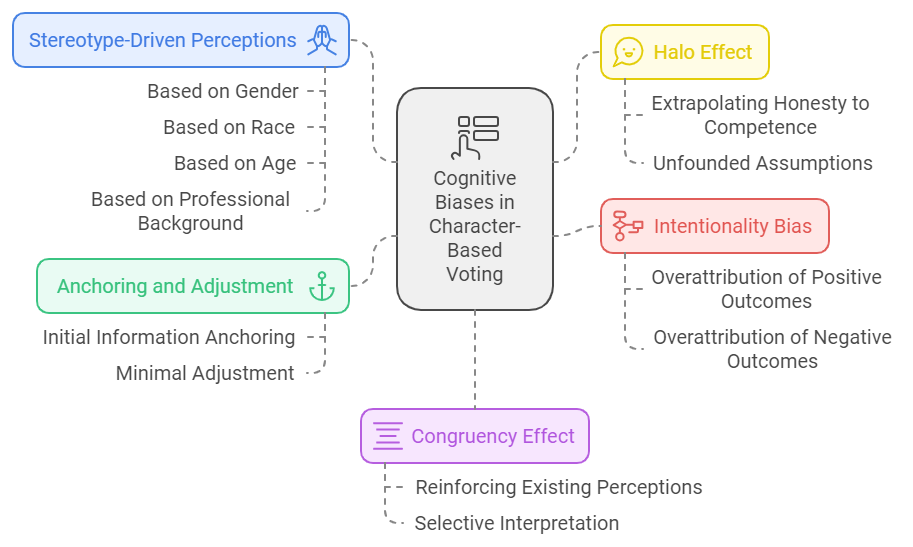

Cognitive Biases Influencing Character-Based Voting: Several psychological tendencies come into play when voters evaluate candidates based on perceived character:

- Halo Effect: This cognitive bias leads voters to extrapolate a candidate’s positive trait to other unrelated characteristics. For instance, a candidate’s perceived honesty might lead voters to assume they are also competent in economic policy, even without supporting evidence.

- Stereotype-Driven Perceptions: Voters often rely on pre-existing stereotypes when assessing candidates. These can be based on various factors such as gender, race, age, or professional background, potentially leading to unfounded assumptions about a candidate’s capabilities or character.

- Intentionality Bias: There’s a tendency among voters to interpret candidates’ actions as intentional and premeditated, even when they might be accidental or circumstantial. This can lead to overattribution of both positive and negative outcomes to a candidate’s deliberate choices.

- Anchoring and Adjustment in Impression Formation: Initial impressions of a candidate can have a disproportionate influence on subsequent evaluations. Voters often anchor their opinions on early information or first encounters, adjusting their views only slightly as new information emerges.

- Congruency Effect in Information Processing: Once voters form an initial impression of a candidate, they tend to respond more favorably to information that aligns with this impression. This bias can lead to a selective interpretation of new information, reinforcing existing perceptions.

Illustrative Scenarios: Consider a voter who is captivated by a candidate’s charismatic public speaking. Due to the halo effect, they might automatically assume this candidate possesses strong leadership skills and policy expertise, despite a lack of concrete evidence. In another instance, a minor verbal slip-up by a candidate might be interpreted as a significant character flaw due to intentionality bias, potentially overshadowing their actual policy positions or qualifications.

Cognitive Biases: The Invisible Architects of Electoral Decision-Making

Cognitive biases are deeply ingrained patterns of deviation from rationality in judgment, inherent to human decision-making processes. In the context of voting behavior, these biases can significantly influence electoral choices, often leading voters to make decisions that may not align with their true preferences or best interests. These mental shortcuts, while efficient in many everyday situations, can introduce systematic errors in the complex arena of political decision-making.

Understanding these biases is crucial for both voters and political analysts, as they shape the landscape of democratic participation in ways that are often subtle yet profound. By recognizing these cognitive tendencies, we can strive for more informed and deliberate decision-making in the electoral process.

- Heuristics in Voting: The Double-Edged Sword of Mental Shortcuts: While heuristics enable voters to navigate the often overwhelming complexity of political issues and candidate choices, they can also lead to oversimplification and potentially flawed judgments. These mental shortcuts, though invaluable for quick decision-making, may result in systematic errors when applied to the nuanced landscape of electoral politics.

- Misleading Perceptions: The Pitfalls of Cognitive Distortions: Cognitive biases can profoundly affect how voters interpret political information, potentially leading to misaligned choices. These distortions in perception and judgment can cause voters to support candidates or policies that may not truly represent their interests or values, underscoring the importance of critical thinking and self-awareness in the voting process.

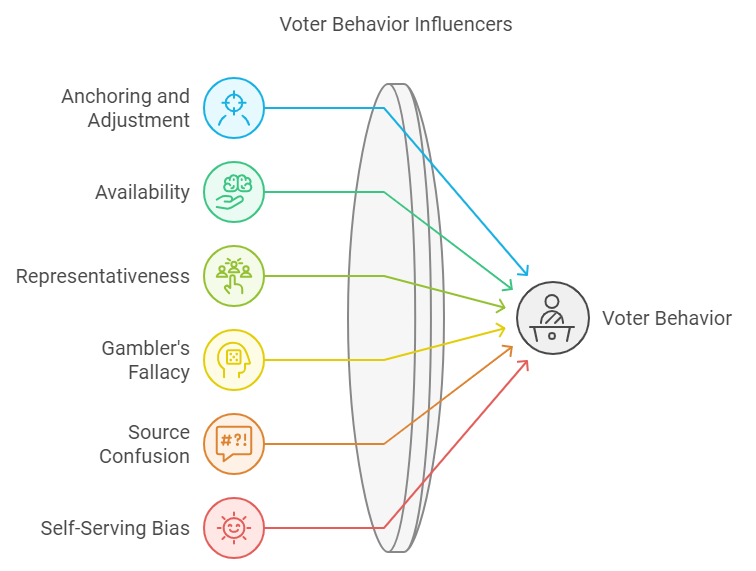

Key Cognitive Biases Influencing Electoral Behavior:

- Anchoring and Adjustment Heuristic: This bias leads voters to rely heavily on the first piece of information encountered (the “anchor”) when making decisions. In political contexts, early impressions of a candidate or initial policy proposals can disproportionately influence subsequent judgments, even in the face of new, contradictory information.

- Availability Heuristic: Voters tend to base their judgments on information that is readily available in memory, which is often influenced by recent or emotionally charged events. This can lead to overestimating the likelihood or importance of issues that have received significant media coverage, potentially skewing electoral priorities.

- Representativeness Heuristic: This bias involves judging the probability of an event or outcome based on how closely it resembles a prototypical case, often ignoring relevant statistical information. In voting, this can manifest as assuming a candidate who fits a certain stereotype will perform better in a particular role, regardless of their actual qualifications or track record.

- Gambler’s Fallacy: The mistaken belief that if something happens more frequently than normal during a given period, it will happen less frequently in the future (or vice versa). In electoral contexts, this might lead voters to believe that if their preferred party has lost several elections, they’re “due” for a win, ignoring the independence of each electoral event.

- Source Confusion: This occurs when voters have difficulty recalling the origin of information, potentially leading to reliance on unreliable or biased sources. In the age of information overload and “fake news,” this bias can significantly impact voter perceptions and decisions.

- Self-Serving Bias: The tendency to attribute positive outcomes to one’s own actions and negative outcomes to external factors. In voting behavior, this can manifest as voters taking credit for positive political developments while blaming others for negative ones, potentially distorting their evaluation of incumbent performance.

- Superiority Bias (Better-Than-Average Effect): This bias leads individuals to overestimate their own abilities or qualities compared to others. In the context of voting, it might result in overconfidence in one’s political knowledge or decision-making abilities, potentially leading to less thorough research or consideration of alternative viewpoints.

Illustrative Examples:

- A voter might overestimate a candidate’s chances of winning based on recent favorable news coverage, exemplifying the availability heuristic. This could lead to complacency in voting or misallocation of campaign support.

- Due to the gambler’s fallacy, a voter might believe that because their party has lost several consecutive elections, they’re statistically “due” for a win in the upcoming one. This flawed reasoning could influence voting behavior or campaign strategy, ignoring the actual factors influencing each unique election.

- The anchoring effect might cause a voter to form a strong initial impression of a candidate based on their first public appearance or policy statement. Subsequent information, even if contradictory, may be interpreted in a way that confirms this initial anchor, potentially leading to a skewed overall assessment.

By recognizing these cognitive biases and their potential impacts on electoral decision-making, voters can strive for more rational and informed choices. Political analysts and campaign strategists, too, can benefit from understanding these psychological tendencies, developing strategies that either mitigate their negative effects or, in some cases, leverage them for more effective communication and voter engagement.

Emotions: The Powerful Force Shaping Electoral Decisions

Emotions play a pivotal and often underestimated role in shaping voter behavior, frequently overshadowing logical analysis and rational decision-making processes. The interplay between emotions and cognitive processes in the electoral context is complex and multifaceted, with far-reaching implications for democratic outcomes.

- Hope and Fear: The Twin Engines of Electoral Motivation: Candidates who successfully evoke strong emotional responses, particularly hope for a better future or fear of potential threats, can wield significant influence over voter decisions. These emotions can serve as powerful motivators, driving voter turnout and shaping policy preferences.

- Emotional Appeals: The Art of Visceral Connection: Political campaigns have long recognized the potency of emotional engagement, crafting messages that resonate on a deeply personal level. By tapping into voters’ aspirations, anxieties, and values, campaigns can forge strong connections that transcend policy details or ideological considerations.

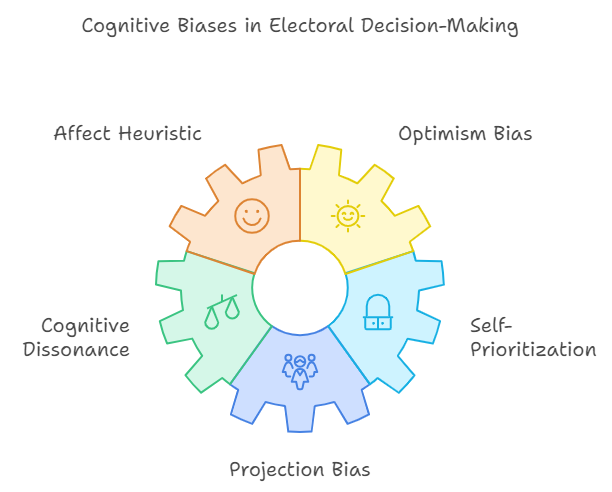

Cognitive Biases Amplifying Emotional Influences: Several psychological tendencies interact with emotions to shape electoral behavior:

- Affect Heuristic: This mental shortcut allows emotions to guide judgments and decisions, often at the expense of rational evaluation. In the voting booth, a candidate who evokes positive feelings may be favored over one with stronger qualifications but less emotional appeal.

- Optimism Bias: The tendency to overestimate the likelihood of positive events can lead voters to have unrealistic expectations about a candidate’s ability to implement promised changes. This bias can be particularly influential when combined with hope-inspiring campaign rhetoric.

- Cognitive Dissonance: When faced with information that contradicts their emotionally-held beliefs about a candidate or party, voters may experience psychological discomfort. To alleviate this dissonance, they often engage in rationalization, dismissing or reinterpreting contradictory evidence to maintain their existing views.

- Self-Prioritization: In evaluating candidates, voters tend to focus on their own emotional responses and personal experiences. This self-centered approach can lead to decisions based more on how a candidate makes them feel rather than on objective assessments of policy proposals or leadership capabilities.

- Projection Bias: Voters often assume that others share their emotional responses and expectations. This can lead to echo chamber effects and reinforce existing beliefs, as voters surround themselves with like-minded individuals who validate their emotional reactions.

Illustrative Scenario: Consider a voter who feels a surge of hope and optimism after hearing a charismatic candidate’s promises of economic revitalization. Due to the interplay of optimism bias and the affect heuristic, this voter might overestimate both the likelihood of these promises being fulfilled and the candidate’s overall competence. If presented with data suggesting the proposed economic plans are unrealistic, cognitive dissonance may lead the voter to dismiss this information, rationalizing that the candidate’s passion and vision will overcome any obstacles. This emotional investment can create a self-reinforcing cycle, where the voter becomes increasingly committed to their choice, interpreting subsequent information through an emotionally-tinted lens.

Information: The Critical Role of Knowledge in Electoral Decision-Making

The availability and quality of information play a pivotal role in shaping voter decisions, with significant implications for the democratic process. Access to comprehensive, accurate, and diverse information sources empowers voters to make informed choices that align with their values and interests. Conversely, limited access or exposure to misinformation can lead to misguided electoral decisions.

- Informed Voting: Voters with access to high-quality, diverse information sources are better equipped to make decisions that accurately reflect their preferences and values. This informed approach contributes to a more robust democratic process.

- Cognitive Shortcuts in Information Processing: In the face of information overload or scarcity, many voters resort to mental shortcuts or heuristics to simplify complex political landscapes. While these shortcuts can be efficient, they may also lead to oversimplification of nuanced issues.

Cognitive Biases Influencing Information Processing in Electoral Contexts:

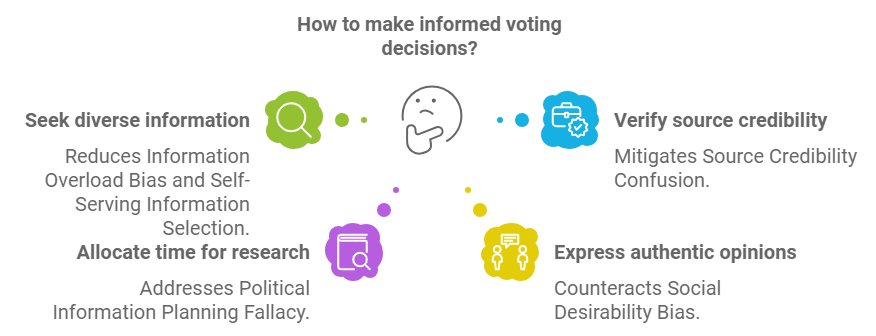

- Information Overload Bias: The tendency to seek excessive information, potentially leading to decision paralysis or avoidance of making a choice altogether. This can result in voter apathy or last-minute, poorly considered decisions.

- Anchoring Effect in Political Information: Initial exposure to information about a candidate or policy can disproportionately influence subsequent judgments, even in the face of new, contradictory evidence. This bias can lead to entrenched opinions that are resistant to change.

- Source Credibility Confusion: In the age of social media and information abundance, voters may inadvertently attribute information to credible sources when it originated from unreliable or biased ones. This misattribution can lead to the propagation of misinformation and influence voting behavior.

- Political Information Planning Fallacy: Voters often underestimate the time and effort required to become well-informed on complex political issues. This can result in superficial understanding and reliance on oversimplified narratives.

- Self-Serving Information Selection: The tendency to prioritize and seek out information that aligns with one’s existing beliefs or serves personal interests. This bias can create echo chambers and reinforce polarization in the electorate.

- Social Desirability Bias in Information Seeking: When seeking political information, individuals may be inclined to express opinions or seek information that they believe will be viewed favorably by others. This can lead to a disconnect between public expressions and private voting behavior.

Illustrative Scenario: Consider a voter who encounters a provocative headline about a political candidate on social media. Due to the anchoring effect, they form a strong initial opinion based on this limited information. Despite the availability of more comprehensive and nuanced information from reputable sources, the voter may struggle to adjust their initial judgment significantly. Furthermore, influenced by the planning fallacy, they might underestimate the complexity of the candidate’s policy proposals, leading to an oversimplified understanding of the electoral landscape. This combination of biases can result in a voting decision that may not accurately reflect the voter’s true preferences or the candidate’s actual positions.

Social Groups: The Identity Factor in Electoral Decision-Making

Social identities and group memberships exert a profound influence on voting behavior, shaping preferences, loyalties, and decision-making processes in complex ways.

- Group Representation and Advocacy: Voters often gravitate towards candidates who they perceive as champions of their group’s interests, values, and concerns. This preference can stem from a desire for representation, a belief in shared experiences, or an expectation of favorable policies.

- Solidarity and Group Loyalty: The bonds of group membership can create a strong sense of loyalty that sometimes supersedes individual policy preferences or ideological considerations. This allegiance can lead voters to support candidates or policies primarily because of their association with the group, even if they might disagree on specific issues.

Cognitive Biases Influencing Group-Based Voting: Several psychological tendencies interact with group identities to shape electoral behavior:

- Groupthink: The desire for harmony and conformity within a group can lead to irrational or poorly considered decision-making. In electoral contexts, this might manifest as uncritical acceptance of a group’s preferred candidate or policy positions.

- In-group Bias: The tendency to favor members of one’s own group can lead to automatic support for candidates who share group membership, potentially overlooking more qualified alternatives from other groups.

- Stereotype-Based Reasoning: Voters may apply generalized beliefs or expectations based on group membership to individual candidates, potentially leading to oversimplified or inaccurate assessments.

- Ownership Bias: Ideas or policies originating within one’s group may be valued more highly simply due to their source, regardless of their objective merits.

- Endowment Effect in Policy Evaluation: Policies or proposals associated with one’s group may be perceived as inherently more valuable or effective, leading to resistance against alternative approaches.

- Reactive Devaluation in Political Discourse: Proposals or ideas from opposing groups may be automatically dismissed or undervalued, hindering constructive dialogue and compromise.

Illustrative Scenario: Consider a voter deeply identified with a particular social group. When evaluating policy proposals, they might instinctively favor those originating from their group (ownership bias), assigning them higher value (endowment effect) even if objectively similar to proposals from other groups. This voter might also overlook potential shortcomings in their group’s preferred candidate, dismissing criticism as biased attacks (in-group bias). Simultaneously, they might reflexively reject proposals from opposing groups, even if those ideas align with their personal interests (reactive devaluation). This complex interplay of biases can lead to voting decisions that prioritize group loyalty over individual policy preferences or objective candidate qualifications.

Moral Obligation: The Civic Duty and Its Psychological Underpinnings

For a significant portion of the electorate, the act of voting transcends mere political participation; it becomes a moral imperative deeply rooted in their sense of civic duty. This perspective persists regardless of the perceived impact of their individual vote on the overall electoral outcome.

- Civic Responsibility as a Driving Force: The belief in active participation in the democratic process serves as a powerful motivator for these voters. This conviction often remains steadfast even in the face of disillusionment with the political system or specific candidates.

- Societal Expectations and Cultural Norms: The collective expectations of a society can exert considerable pressure on individuals to engage in the voting process. These norms, often deeply ingrained, contribute to the perception of voting as a fundamental civic obligation.

Cognitive Biases Influencing the Sense of Moral Obligation: Several psychological tendencies interact with the concept of civic duty to shape voting behavior:

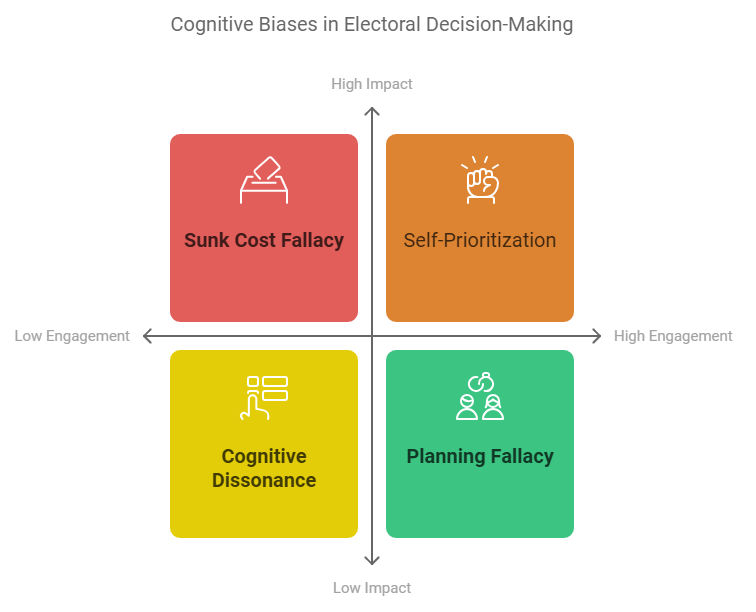

- Sunk Cost Fallacy in Civic Engagement: Voters may feel compelled to continue participating in elections due to their past investment of time and effort in the political process, even when they perceive diminishing returns.

- Self-Prioritization in Democratic Participation: Individuals often prioritize their sense of duty and self-image as responsible citizens over practical considerations such as the immediate impact of their vote or personal inconvenience.

- Cognitive Dissonance in Electoral Behavior: The act of voting can serve as a means to align one’s actions with deeply held beliefs about civic responsibility, thereby reducing psychological discomfort that might arise from non-participation.

- Planning Fallacy in Electoral Participation: Voters frequently underestimate the time and effort required to fully engage in the electoral process, including researching candidates, understanding complex issues, and navigating voting procedures.

- Status Quo Bias in Voting Patterns: The tendency to maintain established voting habits can reinforce the sense of moral obligation, making it psychologically challenging to deviate from past participation.

Illustrative Scenario: Consider a voter who has consistently participated in every election for decades. Despite growing cynicism about the political system, they feel a strong compulsion to vote in the upcoming election. This behavior can be attributed to multiple cognitive biases:

- The sunk cost fallacy leads them to continue voting because they’ve “always done so,” viewing past participation as an investment that justifies future engagement.

- Cognitive dissonance plays a role as the act of voting helps reconcile their actions with their self-image as a responsible citizen, even if they doubt the efficacy of their individual vote.

- The planning fallacy might cause them to underestimate the effort required to make an informed choice, potentially leading to last-minute, less considered decisions.

- Status quo bias reinforces their voting habit, making non-participation feel like a significant and uncomfortable departure from their established norm.

This complex interplay of psychological factors underscores how deeply ingrained the sense of moral obligation can be in shaping electoral behavior, often transcending rational cost-benefit analyses of voting impact.

Strategic Reasons: The Tactical Vote and Its Implications

Strategic voting is a complex decision-making process where voters make choices based not solely on their primary preferences, but on a broader set of considerations that take into account the intricacies of the electoral landscape and potential outcomes.

- Preventing Undesirable Outcomes: This involves the deliberate selection of a candidate who may not be the voter’s first choice, but who has a higher probability of winning against a candidate the voter strongly opposes. This approach requires careful analysis of polling data and a nuanced understanding of the electoral system.

- Multi-Candidate Dynamics: In electoral scenarios featuring multiple viable candidates, strategic voting becomes particularly prevalent and influential. Voters must navigate a complex web of potential outcomes, considering not just their own preferences but also the likely behavior of other voter groups.

Cognitive Biases Influencing Strategic Voting: Several psychological factors come into play when voters engage in tactical decision-making:

- Loss Aversion: The psychological tendency to prioritize avoiding losses over acquiring equivalent gains can strongly motivate voters to act strategically. This bias often leads to defensive voting patterns aimed at preventing worst-case scenarios rather than optimizing for ideal outcomes.

- Reactive Devaluation: This bias can cause voters to automatically dismiss or undervalue proposals and qualities of candidates they’ve decided not to support, even if these proposals align with the voter’s interests. This can lead to a skewed perception of the political landscape and potentially suboptimal voting decisions.

- Superiority Bias: Voters may overestimate their ability to accurately predict electoral outcomes and the effectiveness of their strategic choices. This overconfidence can lead to misguided tactical voting that doesn’t align with the voter’s true interests or the actual dynamics of the election.

- Gambler’s Fallacy: Some voters mistakenly believe that past election results directly influence future outcomes, leading to flawed strategic calculations. This can result in misguided attempts to “balance” political power or anticipate swings in public opinion.

Illustrative Scenario: Consider a voter in a three-way race who typically supports a minor party candidate. Polls suggest their preferred candidate has little chance of winning, while the race between the two major party candidates is close. Influenced by loss aversion, the voter might reluctantly support a major party candidate they don’t fully endorse to prevent the victory of a candidate they strongly oppose. This decision might be further reinforced by superiority bias, leading the voter to believe their strategic choice will be particularly impactful. However, if many voters make similar calculations, it could lead to unexpected outcomes, highlighting the complex nature of strategic voting in shaping electoral results.

Overconfidence: The Perilous Illusion of Knowledge in Electoral Decision-Making

Overconfidence, a cognitive bias that plagues many aspects of human decision-making, can have particularly significant consequences in the realm of electoral choices. This phenomenon occurs when voters develop an inflated sense of their own understanding and knowledge about political issues, candidates, and potential outcomes. Such misplaced confidence can lead to a cascade of misjudgments and ill-informed decisions that may ultimately impact the democratic process.

- Misjudging Impact and Effectiveness: Voters afflicted by overconfidence often overestimate their ability to accurately predict electoral outcomes or the effectiveness of proposed policies. This can result in support for unrealistic promises or dismissal of pragmatic solutions that might actually be more beneficial.

- Complacency and Voter Apathy: When overconfidence intersects with a sense of certainty about electoral results, it can breed a dangerous complacency. Voters might abstain from participating, believing their preferred outcome is assured, potentially altering the election’s outcome.

- Resistance to New Information: Overconfident voters may be less likely to seek out or seriously consider new information that challenges their existing beliefs, leading to a stagnation of political understanding and a resistance to changing circumstances.

Cognitive Biases Amplifying Overconfidence: Several interrelated psychological tendencies contribute to and exacerbate the problem of overconfidence in electoral decision-making:

- Overconfidence Effect: This fundamental bias leads individuals to have a degree of confidence in their judgments, abilities, and knowledge that far exceeds their actual competence or accuracy. In the political arena, this can manifest as voters believing they have a comprehensive understanding of complex issues based on limited information.

- Planning Fallacy: Voters often underestimate the time, effort, and resources required to fully comprehend multifaceted political issues or to evaluate candidates’ qualifications and proposed policies thoroughly. This can lead to oversimplified views and hasty judgments.

- Optimism Bias: The tendency to believe that positive outcomes are more likely than negative ones can skew voters’ perceptions of electoral prospects. This bias might cause supporters of a particular candidate or party to overestimate their chances of victory, potentially influencing their voting behavior or level of engagement.

- Self-Serving Bias: In the context of political decision-making, this bias can lead voters to attribute positive political outcomes to their own choices or preferred candidates while dismissing negative results as the fault of external factors or opposing groups. This selective attribution can reinforce overconfidence in one’s political judgments.

- Dunning-Kruger Effect: This cognitive bias causes individuals with limited knowledge or expertise in a given domain to overestimate their abilities. In politics, it can result in voters with superficial understanding of complex issues believing they have deep insight, leading to misplaced confidence in their electoral choices.

Illustrative Scenarios: Consider these examples of how overconfidence can manifest in electoral behavior:

- A voter, buoyed by optimism bias and the overconfidence effect, may be so certain of their preferred candidate’s impending victory that they choose not to vote, believing their participation unnecessary. If many supporters share this mindset, it could potentially alter the election’s outcome.

- Due to the planning fallacy and Dunning-Kruger effect, a voter might overestimate their understanding of a complex economic policy after reading a brief summary. This misplaced confidence could lead them to strongly support or oppose the policy without fully grasping its implications or potential consequences.

- Influenced by self-serving bias, a voter might attribute positive economic indicators to their chosen candidate’s policies while dismissing negative trends as unrelated or caused by external factors. This selective interpretation reinforces their confidence in their political choices, potentially blinding them to important realities.

Recognizing and mitigating the effects of overconfidence in electoral decision-making is crucial for maintaining a well-informed and engaged electorate. Voters should strive to approach political issues with humility, seek diverse sources of information, and remain open to changing their minds in light of new evidence. By acknowledging the limits of our own understanding and the complexity of political issues, we can work towards more thoughtful and nuanced electoral participation.

Conclusion

Understanding cognitive biases and the various factors influencing electoral decision-making is crucial for fostering a more informed electorate. While expecting all voters to be perfectly rational is unrealistic, awareness of these influences can help individuals reflect on their decision-making processes. By recognizing the roles of ideology, party identification, candidate character, emotions, information access, social identities, moral obligations, strategic considerations, and overconfidence, voters can strive to make choices that more accurately reflect their true preferences and positively contribute to the democratic process.

As future elections approach, take time to reflect on what influences your voting decisions. Seek diverse sources of information, question your assumptions, and be mindful of cognitive biases that may sway your choices. Remember, your vote isn’t just a personal decision—it’s a contribution to the collective future of your community and nation.

FAQ: Heuristic Shortcuts in Political Decision Making

1. What are heuristic shortcuts and how do they affect political decisions?

Heuristic shortcuts are mental shortcuts that people use to make quick decisions, especially in complex situations like voting. These shortcuts simplify the decision-making process by relying on readily available information and past experiences rather than in-depth analysis. While heuristics can be efficient, they can also lead to cognitive biases, which are systematic errors in thinking that can distort our judgments and lead to irrational choices. For example, a voter might use the availability heuristic to decide which candidate is best by focusing on the candidate they have seen the most in the news, even if that candidate’s policies don’t align with their beliefs.

2. What is the availability heuristic and how does it apply to political decisions?

The availability heuristic is a mental shortcut that leads people to judge the likelihood of an event based on how easily they can recall examples of it. In politics, this means that voters may overestimate the importance of issues that are highly publicized or emotionally charged, even if those issues are not statistically representative of the overall political landscape. For instance, a voter might be more likely to support a candidate who focuses on crime prevention if they have recently seen a news report about a local crime, even if crime rates are generally low.

3. How does the representativeness heuristic influence voters’ choices?

The representativeness heuristic is a mental shortcut where people make judgments about the probability of an event based on how similar it is to a prototype they have in mind. In politics, this can lead voters to choose candidates who fit a certain stereotype or who they perceive as being “typical” of a particular party or ideology, even if those candidates are not the most qualified or best suited for the job. For example, a voter might choose a candidate simply because they look and sound “presidential,” even if that candidate lacks the necessary experience.

4. What is perseverance bias and how does it affect political opinions?

Perseverance bias is the tendency for people to cling to their beliefs even when presented with evidence that contradicts them. This bias is particularly strong when it comes to political opinions, as people often identify strongly with their political views and see them as a core part of their identity. Perseverance bias can lead to political polarization, as people become less willing to consider alternative viewpoints or to engage in constructive dialogue with those who hold different beliefs.

5. How does confirmation bias impact political decision-making?

Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out and interpret information that confirms our preexisting beliefs, while ignoring or downplaying information that contradicts them. In politics, confirmation bias can lead people to become trapped in “echo chambers,” where they are only exposed to information that reinforces their existing political views. This can lead to extreme and inflexible political beliefs, as people become increasingly isolated from opposing viewpoints.

6. What role does the ‘influence of presumed influence’ play in shaping voter behavior?

The ‘influence of presumed influence’ suggests that individuals are swayed not only by the direct effects of media messages, but also by their perceptions of how those messages affect others. For example, even if a voter is not personally persuaded by a piece of propaganda, they might be less likely to protest if they believe that the propaganda is effective at persuading others to support the regime. This perceived influence on others can create a chilling effect on dissent, as people become hesitant to express their views publicly.

7. How can group membership and social identities impact political decisions?

Group membership and social identities play a powerful role in shaping political decisions. People often feel a strong sense of loyalty to their social groups, and they may be more likely to support candidates or policies that they believe will benefit their group, even if those candidates or policies are not in their best interests as individuals. This can lead to “identity politics,” where people vote based on their group affiliations rather than on issues or policy positions.

8. How can voters mitigate the impact of cognitive biases on their political decisions?

While it’s impossible to completely eliminate cognitive biases, being aware of their existence is a crucial step toward making more informed political decisions. Voters can try to mitigate the impact of biases by seeking out information from diverse sources, considering alternative viewpoints, and being willing to challenge their own assumptions. Engaging in open and honest conversations with people who hold different political views can also help to broaden perspectives and reduce the influence of confirmation bias. By being more mindful of the ways in which cognitive biases can distort our thinking, we can strive to make more rational and informed political choices.

Leave a Reply